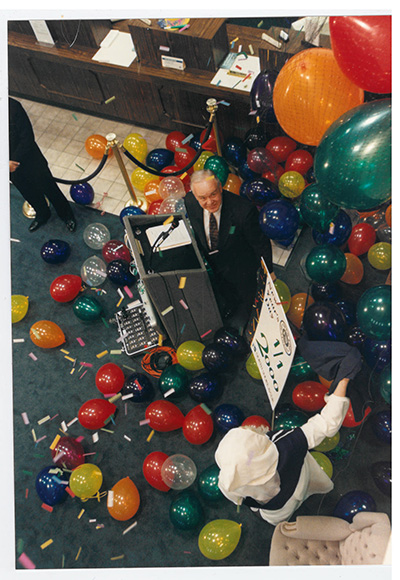

Father Time reassures a customer that North Shore Bank is ready for Y2K at a special event at the Shorewood branch in March 1999.

Twenty-three years ago this month, the world breathed a sigh of relief as New Year’s Day passed without any major disruption. For several years prior, experts had warned that the so-called “Y2K error” could cripple computer systems around the globe, bringing entire economies and governments to their knees.

By the time the ball dropped in Times Square, however, IT professionals were confident they had the problem licked. North Shore Bank was so sure, we built an entire marketing campaign around our Y2K readiness, promising our branches would be open for business on January 1, 2000. And they were.

“I don’t remember clearly whose idea it was to promote that North Shore would be open on New Year’s Day, but we thought it would send a clear message that the bank was totally prepared, and that our customers didn’t have to worry about the security of their funds,” says Steve Steiner, who, before retiring in 2014, served as senior vice president in charge of retail banking at the turn of the millennium.

“I don’t remember clearly whose idea it was to promote that North Shore would be open on New Year’s Day, but we thought it would send a clear message that the bank was totally prepared, and that our customers didn’t have to worry about the security of their funds,” says Steve Steiner, who, before retiring in 2014, served as senior vice president in charge of retail banking at the turn of the millennium.

The Y2K issue resulted from 20th-century computer programmers’ need to save space. Back then, digital storage was typically measured in kilobytes and megabytes, and only rarely in the gigabytes and terabytes common today. As such, in a lot of software code, years were represented by only their last two digits — for instance, 1999 would be written as 99. That meant those systems — used by countless industries and agencies worldwide — couldn’t tell the difference between the year 2000 and the year 1900.

Nobody could say with any certainty what would happen if all of that code wasn’t fixed, but doomsayers predicted the collapse of banking systems and financial markets, among other disasters. “Pundits raised the prospect of dire consequences and cast doubt on the readiness of the country’s computer systems,” Steve recalls.

Today, the consensus seems to be that the Y2K bug was probably not as serious a problem as it was made out to be, but also that the incessant alarming predictions galvanized industries to address the glitch, averting a potential crisis. Regardless of how much damage the bug might actually have caused, though, consumers’ fears at the time were very real.

Getting ahead of the bug

“We started early in preparing for Y2K in order to ensure we covered as many topics and possible points of failure as we could,” says VP customer support Jude Lengell, who was in charge of branch sales and administration at the time. “We worked with all appropriate third-party external partners to ensure they were ready and to understand what updates or changes we needed to make with system settings. We also created training materials for our internal teams on how to answer possible questions from our customers.”

Indeed, a message from then-president Jim McKenna in the Spring 1999 issue of Shorelines (a quarterly publication back then) reports: “In mid-1997, we initiated aggressive action. In a single year, we invested over $5 million to upgrade our main processor and ensure that provider software, hardware, and other microchip-dependent equipment and systems were warranted to be Year 2000–compliant.”

Steve Steiner at the Shorewood balloon drop.

In March 1999, we put out a press release announcing that North Shore Bank would be open for business on January 1, 2000. Responding to calls for Americans to empty their bank accounts — out of fear that the Y2K bug would cause funds to evaporate without a trace — Steve was quoted as assuring our customers that “the best and safest place for their money — in the Year 2000 or at any time — is in our bank, rather than their home.”

The press release was accompanied by a balloon drop at our Shorewood office, featuring Steve, deputy secretary Jim Huff of Wisconsin’s Department of Financial Institutions, and an actor dressed as Father Time, who spoke with customers about their concerns and assured them that North Shore Bank was on top of things. A similar press conference event was held at our Allouez office. As a result, newspapers and local TV and radio stations in the Milwaukee and Green Bay areas prominently covered the event.

“We got very positive coverage from the media, which touted North Shore’s efforts to get in front of this potential issue. Customers appreciated that the bank was sufficiently confident in its preparedness that it would take the extraordinary step of being open on a national holiday,” Steve says.

Our ensuing Y2K readiness marketing campaign included a dedicated logo and materials like a brochure of financial safety tips specifically related to the bug. This was critical because even though IT teams had been working overtime for months to rectify the Y2K bug, the apocalyptic atmosphere created a massive opening for scammers to take advantage of a panicked public. “Watch out for special investment opportunities that offer ‘the chance of the century,'” our brochure warned. It also noted: “The ‘opportunity’ to buy books and subscriptions to magazines and newsletters that will ‘save you from the crisis’ is just another scheme to get your money.”

Our ensuing Y2K readiness marketing campaign included a dedicated logo and materials like a brochure of financial safety tips specifically related to the bug. This was critical because even though IT teams had been working overtime for months to rectify the Y2K bug, the apocalyptic atmosphere created a massive opening for scammers to take advantage of a panicked public. “Watch out for special investment opportunities that offer ‘the chance of the century,'” our brochure warned. It also noted: “The ‘opportunity’ to buy books and subscriptions to magazines and newsletters that will ‘save you from the crisis’ is just another scheme to get your money.”

An article in the Summer 1999 issue of Shorelines mentions that we were also keeping customers informed by including mailers about our Y2K readiness with their monthly statements.

New millennium, no worries

As you know, the story had a happy ending. All 37 of North Shore Bank’s branches were open from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Saturday, January 1, 2000.

The Shorewood, Westgate, and Ashwaubenon offices also featured media availability events that day, with party decorations and treats, giving journalists a chance to see that our systems were fully functional — and that our customers were very happy. “Customers who came in expressed that to our staff,” Steve says.

Of course, we didn’t leave anything to chance. Our Information Systems team and other staff members spent their New Year’s Eve at their desks. “At the stroke of midnight, we had folks checking their assigned testing systems, platforms, and applications to ensure everything looked good,” Jude remembers. “The time we put into it paid off.”

Steve agrees. “It was a particularly happy new year when we knew there were no problems.”